Mental Health Awareness Month

My mother, she knew what it’s like to feel like you’re drowning, with the exception of these moments, these very rare, brief instances, in which you suddenly remember… you can swim.

Growing up, home didn’t feel like home. It felt confusing and unstable. My mother was complicated—my biggest critic and my loudest supporter. My brother and I had different fathers, which added a strange tension to everything. My biological father was cut off from me when I was young. My brother was the first person I ever looked up to—and also the first to hurt me. That left a scar early on.

By the time I was a kid, I had already built a kind of emotional armor, like a scab over my heart. A survival instinct. But it wasn’t just the big moments that hurt—it was the constant picking away at that healing. Because of the chaos at home, I missed a lot of school and felt like an outsider in my own life. I started therapy young and was in and out of different systems—psych wards, medications, diagnoses. I was 11 the first time I was hospitalized for my mental health.

When I was 17, I made the decision to leave home for good. I started couch surfing, and eventually found some stability living under the roof of a friend’s father who took me in. It wasn’t perfect, but it was safe—and it gave me the space I needed to start building a future. Thankfully, during high school, a few key staff members saw what I was going through. They didn’t just look the other way. They helped connect me to therapy and other supports, and ultimately played a role in helping me leave my abusive home for good. With their help and through the programs they connected me with I was able to stay in school, access mental health care, and begin to envision a life beyond survival.

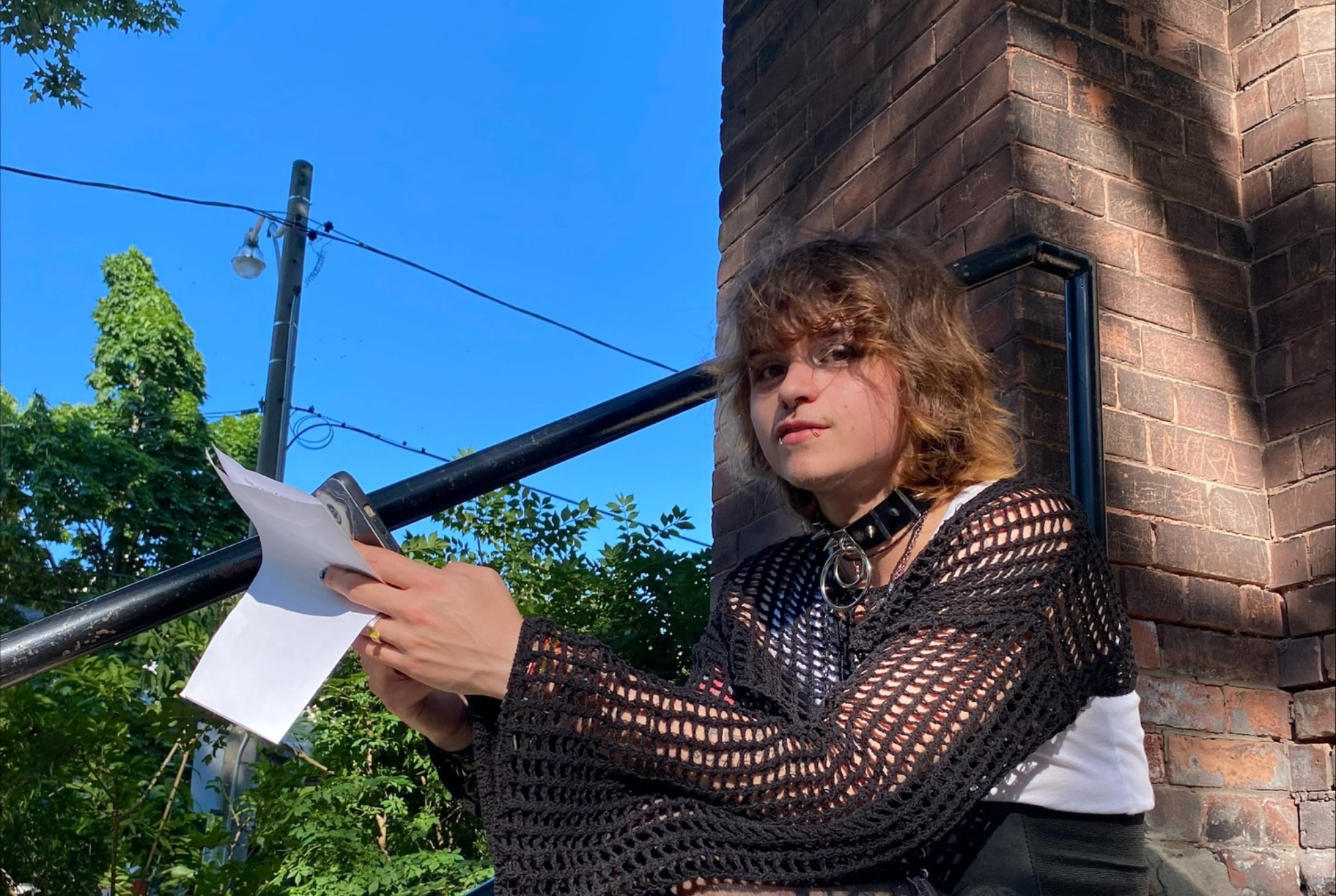

It took me six years to finish high school. Six. But I did it. I graduated at 20 years old and somehow walked away with three scholarships. That was the push I needed. That was the beginning of possibility. There were people and organizations who stepped in when I needed them most—teachers, support workers, and community programs like StepStones for Youth. Each one helped me put together the pieces of a new life. They didn’t fix me, but they gave me the space to breathe—and reminded me that what I was experiencing didn’t have to be the end of my story.

Recently, I completed a culinary program at George Brown College, was awarded two scholarships, finished a 150-hour internship, and landed a full-time position. For the first time, I signed a lease—with my childhood best friend and with my high school sweetheart. This life I’m living now was once unimaginable.

I still have bad days. Recovery isn’t a straight line. But the fact that I’m here, writing this, is proof that it can get better. If I could talk to my younger self, I’d tell him to keep going. And if I could ask my older self anything, I think it would be: Why were we in such a rush to grow up?

To anyone reading this who’s struggling, I want to say: Don’t give up. Push through the droughts. Channel the inevitable disappointments back into your craft. Break molds. Think. Create. But most importantly, stay alive. And in the meantime, make it about others. That seems to work. Stay strong. Live on. And power to the local dreamer.